Last week we ended we finished on the schematics for pricing and how physical cargoes are actually exchanged. Today we dive into one of the most crucial parts of commodities trading, risk management. When you move a physical cargo you are exposed to multiple risks, from operational, to legal, to credit risk, and though there are ways to mitigate some of those what often haunts traders is price risk.

To put it simple, price risk is the possibility of losing money on any open position you may have. The idea of trading is to remove as much price risk as you can, but not all, because in essence a trader’s job is to create that risk and managing it accordingly.

Commodity traders are primarily concerned with price differentials, rather than the absolute level of commodity prices (flat prices), hence the need to eliminate this risk is the first thing that comes to mind.

You have risk exposure when you have a position, either long or short, and here we need to make a distinction between being long or short physical vs on price. In commodities parlor, you are either physical short or long depending the nature of your business or geolocation. For example, we say “Europe is long gasoline and short diesel”. Europe as a whole is not a trader (and thanks god for that) but given is regional refinery configurations and proximity to certain crude streams, Europe produces more gasolines than it needs to cover its domestic demand, so it has excess quantities of gasoline, meaning once the internal demand is covered the “unsold” gasoline stockpiles are exposed to changing prices, if the gasoline prices go up, they make money, as in stock trading, they are long the price as well. At the same time, Europe doesn’t make enough diesel to meet the demand and has to import from the open market, we say they are short because they are always buying to cover and exposed to spot, if you look at it from the financial perspective, when diesel prices rise, they lose money, they save money when global prices go down, hence they are short.

Suffices to say that an oil producer is always long crude oil, a refinery is always short crude oil and so are we as end consumers in refined products.

When discussing about price exposure, you are either long, short or flat only when you have a fixed price.

Right when you have price exposure is when “hedging” comes to the table, so what is hedging?

A hedge is a trade or position that is made with the intention of reducing the risk of adverse price movements. Ideally a hedge would consist of taking an offsetting or opposite position in a related derivative such as a futures contract or a swap, for example, you are long one physical cargo of crude oil and you would offset that “length” either selling that same cargo at the same price and same conditions (back-to-back deals) or use the derivatives market to take the opposite position, selling crude oil futures.

The idea of being hedged is that you are neither long or short, you are flat. You don’t care where prices go. You bought 1 million barrels of North Sea Forties at $75 (you are long), your total exposure is now $75 Million, and immediately you sell 1 million barrels of ICE May Brent futures at $75, giving you an exposure of -$75 Millions, so depending on how prices moves while your cargo is in transit you will lose some in some leg of the trade (phys or paper) and compensate in the other.

So, if a trader is neither long or short, how does he make money? To answer that question, we need to revisit the ground rule of risk management, there is not such thing as a perfect hedge (nor you don’t want it to be).

Traders live and die on what is called “Basis Risk” is the differential between the price of a physical commodity and its hedging instrument. Basis risk is the risk of a change in this differential. Hedging exchanges flat price risk for basis risk. When we use WTI futures, Brent futures or Dubai swaps, these are standardized instruments, that more often than not would not match our physical cargoes, the most common issue being a timing mismatch, as futures and swaps have a defined expiration date.

Let’s say today March 26th we load 1 million barrels of Bonny Light in Nigeria with the intention of sending it to Rotterdam, it takes 17-18 days to get there, arriving on April 12th at best, what do we use for hedging? The common answer would be Brent futures, problem is that Brent futures are already trading May deliveries, and this contract last trading day is March 31st . So in order to be 100% offset we need coverage for the 5 remaining days of March, plus 12 days of April when we will sell our cargo, and although there are some weekly swaps we could use (CFDs), but our most likely options are either sell 1 million barrels in May contract and roll to Jun contracts on March 31st, but we don’t know what the rolling spread will be, that’s one basis risk, or just sell 1 mb in the Jun contract, that expires way after we sold our cargo meaning it has different price dynamics, there is a basis.. and probably we are selling our cargo against Dated Brent, which is not the same thing as a Brent future, another basis there.

Let’s see a practical case. Assume you are a trader and you have a term contract with a refinery to lift 500,000 bbls per month of Gasoil in Singapore, the sales contract says price will be determined using current month of Platts Gasoil Swaps, 5 days around the B/L + a premium of $1 per barrel.

So far, we have a commitment to pick up half a million barrels per month, but since we don’t have a price, we don’t have a risk…or at least price risk, should they declare “force majeure” and we already re-sold that cargo, we are screwed… that’s operational risk + legal risk.

Anyway, let’s say we send a vessel (LR1 in this case) and it finishes loading on Wednesday. As we know, we won’t know our final price of our cargo until Friday (2-1-2 days after B/L) How do we hedge that?

We need to identify the pricing period or when our cargo starts pricing, and since it is an average of 5 days, we have 5 different pricing days. 100% of the final price will be the comprised of 5 separate 20% chunks, or 20% per day, or 100,000 barrels, which is equivalent to say we are loading 100kb per day over 5 days, meaning we are going long physical 100kb per day. Hedging is about offsetting so everyday we have a physical exposure, we cancel it taking the opposite position, in this case selling 100kb at the last minute of the trading session, so we end our day long physical and short paper. By the end of the week, you will be long and short equal amounts of barrels. You have a paper position of $ -40,769,000, and your cargo is worth $ 40,769,000, right?

Wrong, you will be invoiced 500kb at $81.54 per barrel plus $1 premium, $ 41,269,000. That difference between what you actually paid and your position in the financial instrument is your basis risk, so effectively you are $500,000 long gasoil cash premiums.

Since you are sending your tanker, you are buying FOB (Free on Board) from the refiner and selling delivered (CIF, CFR, DAP, etc) somewhere, once you have the B/L the cargo is yours to sell.

The best possible scenario, the distillates market in Asia is strong and the spot market is at Platts Sing 10ppm and a cash premium of $2, so 10 or 15 days before going to pick up your cargo you sell that to another desperate buyer, that will send his own vessel on the day the refiner nominates the cargo to you and you now become a FOB seller, just need to make sure you use the same pricing scheme (5 days around B/L), you receive an invoice for the average +$1 and you invoice your client the same average +$2. Easy money.

But is not always that easy, if you find yourself picking up a cargo in summer when demand for “distys” is weak, you could find the spot market is currently at Platts Sing +$0,50, you have to options, to swallow your pride and take the loss of $250k (0.5x500,000) or try to shift your cargo to a better market somewhere else to try to make a profit. That is arbitraging your cargo.

An arb, in essence is a hedge using a different instrument that you would normally use, transforming your cargo in time and space (another location). Since you are moving a cargo through space and time, you will use another benchmark in another delivery period (further in time) so you start looking at prices in different markets. You need some pieces to solve this puzzle though, you need a spot price at origin, a spot price at destination, how long does it take to get there and how much does it cost to get there (freight).

Actually, you need a little bit more data, as you need to know the curve structure of the paper markets (contango, backwardation), since you are holdings barrels for a longer period of time. We call contango when prices for delivery a commodity in the future are higher than today, or backwardation when the price for prompt delivery is higher than delivering it into a future date (grain people call them “Carry” and “Inverse”) anyway, in backwardated markets as we have today you pay a penalty to keep the barrels for longer, so you need to account for that extra cost when doing the calculations.

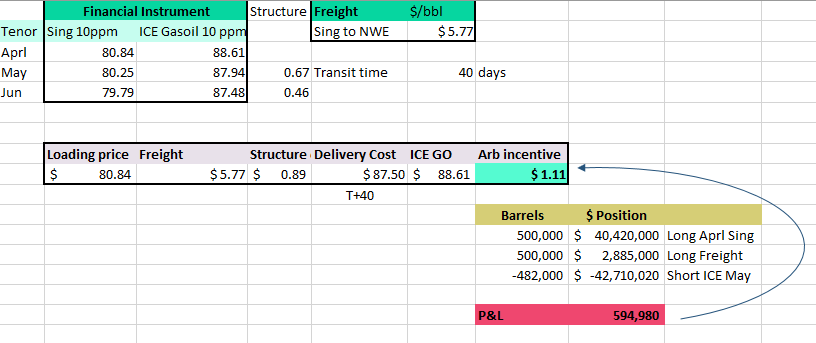

In the example above, we compare the two spot prices, our market (Singapore) and the destination market, in this case Europe. We noted that it takes 40 days to sail from Sing to Rotterdam, so we need an estimate of what the price will be when our cargo lands, so we apply the monthly difference between the paper markets at destination M1 and M2 (0.67) and since our cargo is landing by mid M2, we add extra 10 days. We could use the May futures, but we only need 10 days of May, so you need to add to that end of May prices 20 days of lost backwardation. It works both ways but is easier to do it like the excel.

You haven’t even loaded yet but you have one fixed price already, the freight cost. All we care here is the spread and how we lock in all the prices even before we send our ship to lift the cargo.

Depending on the market, but spot assessments are for cargoes loading 10-15 ahead, and you already know the where the “cash premium” in advance, so knowing you are going to get hit you decide that the arb to Europe $1.11 is good enough, so you lock in everything in the following steps:

You buy Sing paper (you don’t have a cargo yet but you’ll see why in a minute)

You buy (or fix) a ship at a rate (you are long here)

Bear with me on this one, you need to adjust for that “structure cost”, those 89 cents per barrel so instead of selling 500k contracts in May, we optimize the hedging quantity, because we don’t need the full month of May coverage. Trying to keep our $1.11/bbl profit we hedge a smaller quantity at higher prices. 482,000 give or take... by the way, ICE Gasoil trades in $/metric ton, so it’s even harder to get close to the desire amount.

This way you locked the spread by buying and selling paper, an at the moment of lifting your physical cargo, in a couple of weeks time, once you have a fixed price in your cargo, you swap the long exposure that you have in paper, closing that position, so now you are long physical (cargo+freight) and short paper, no matter where the prices go, you have your P&L locked in.

Did you make $1.11/bbl at the end of the day? No, remember you buy at $1 premium over spot, so all you made is $0.11/bbl, which is considerably better than losing $0.5

This is one of the many ways of swapping physical positions with paper positions as these two markets are intertwined.

If this seemed a little complicated, get ready because on the next one we are doing crude arbs and we are doing more math…. and chemistry. Leave your questions below or feel free to chime in.

In the Arb Excel you are using the ICE Gasoil April (88.61) to calculate your short paper position (in cell H14). Wouldn't it be ICE Gasoil May (87.94)?

Also, could you explain how did you reach the 482kb volume? Thanks so much for this stuff!

Explain more about the structure if you would. Between Apr-May and May-Jun. Also how do you get the 89cents structure. Cheers Bandit